Sender Policy Framework (SPF) is a fundamental component of modern e-mail authentication, designed to reduce the risk of spoofing and phishing attacks. By publishing a DNS record that specifies which mail servers are authorised to send messages on behalf of a domain, SPF allows receiving systems to validate whether an incoming message genuinely originates from the claimed sender. SPF alone does not provide a complete defence against fraudulent email, it remains an essential part of a layered security strategy when used in conjunction with mechanisms such as DKIM and DMARC. In this post, we will focus specifically on SPF, exploring how it works, common pitfalls in configuration and best recommendations for strengthening organisational email security.

Light Bedtime Reading

You can see the SPF related RFC memos and their release dates below. Note that RFC 4408 is dated April 2006. It’s been a hot minute…

-

RFC 4408 – Sender Policy Framework (SPF) for Authorizing Use of Domains in E-Mail, Version 1 (April 2006) – The original standard for SPF.

-

RFC 7208 – Sender Policy Framework (SPF) for Authorizing Use of Domains in E-Mail, Version 1 (April 2014) – Obsoletes RFC 4408; clarifies ambiguities and provides the current standard.

-

RFC 6652 – Sender Policy Framework (SPF) Authentication Failure Reporting Using the Abuse Reporting Format (June 2012) – Describes how SPF failures can be reported back to domain owners using ARF (Abuse Reporting Format).

Sample SPF Record

SPF records are published into DNS and are easily queried by other mail systems on the Internet. SPF are generally pretty boring and contain text that will typically look like this:

v=spf1 ip4:4.152.242.240 include:spf.protection.outlook.com –all

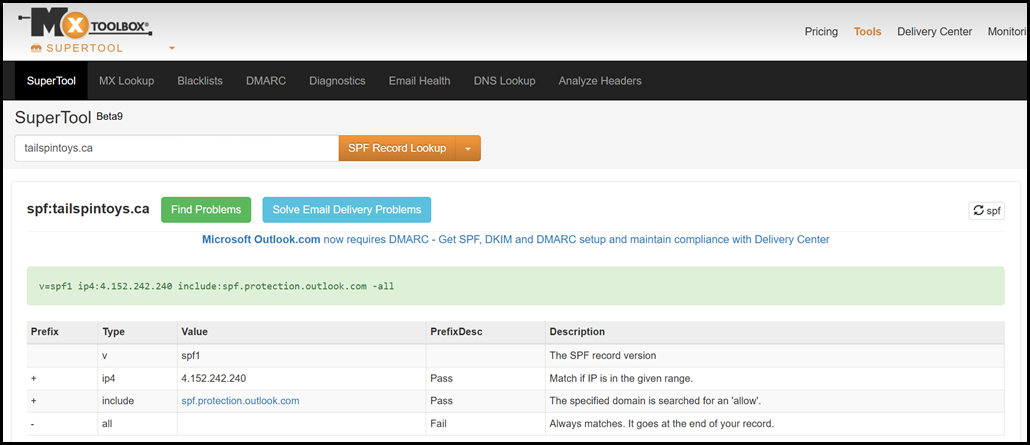

You can retrieve a SPF record using dig, nslookup etc. But using an online tool makes this easier and also provides context. For example, mxtoolbox.com is a popular choice.

The screenshot is the current SPF for tailspintoys.ca. If you really want to use command line, go ahead and use nslookup to retrieve that easily.

Sometimes you may find more interesting ones. We will expand this at the end of the post once we have worked through some of the underlying SPF record requirements.

An example of an “interesting” record is shown below. This could be the SPF record that is present for wingtiptoys.ca when they use a third party SPF service called Relecloud.com

v=spf1 include:%{i}._ip.%{h}._ehlo.%{d}._spf.Relecloud.com ~all

In this case Relecloud.com is a hypothetical SPF record flattening service. It also happens to be a domain that is on the approved list of fictitious companies such as Contoso and Lucerne Publishing.

SPF Record Basics

A SPF record is a regular TXT record in DNS. There used to be a specific SPF record type (99), but that is long depreciated and is not to be used.

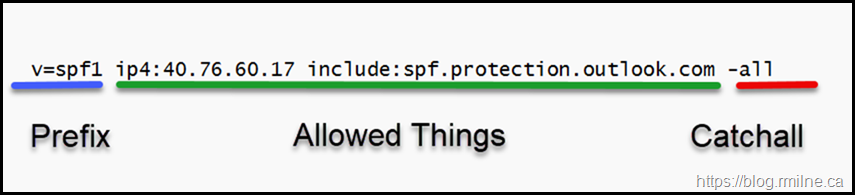

The TXT DNS record will follow a set and known layout. In its simplest form it can be broken down into three main section. Let’s break down the simple SPF record above using colour coded sections.

First Section - The blue section states that this is a SPF record.

Second Section - The green section, in the middle, states who/what is allowed to send as this domain.

Third Section – The red section at the end, states how the rest of the Internet should be treated. This is all of the other systems that are specifically NOT called out in the second (green) section.

In the “Allowed Things” section you will find a range of entries that may or may not be present. The exact items that are present for a given domain will depend on who/what is meant to send as that domain and what is the most effective way to include them. You may see entries in there such as:

-

a

-

mx

-

ptr

-

ip4

-

ip6

-

exists

-

include

SPF Catchall Options

At the end of the SPF record you state what should happen to messages that are not sent from an authorised sender. This is the “catch-all”. In SPF syntax, the "catch-all" at the end of a policy is the all mechanism, and it can be combined with different qualifiers. These qualifiers tell the receiving server how to treat messages that do not match any of the earlier mechanisms in the record. The options are:

?all Neutral Says “no policy”: the domain is not asserting whether mail from unauthorised sources is valid. Effectively tells the receiver to make its own decision. Very meh.

+all Pass (allow everything) This effectively makes SPF meaningless, because all senders are authorised. It is strongly discouraged, though it was sometimes used in the early days for testing.-all Fail (hard fail) A strict policy: anything not explicitly listed in the SPF record should be rejected. This is the most definitive catch-all option.

~all SoftFail Indicates that mail not matching the authorised sources is probably unauthorised, but receivers should accept it and mark it (often with a spam flag). This was the recommended transition option while moving to -all.

To recap the full set of catch-all options for SPF are:

?all, +all, ~all and –all

What Catchall Should I Use

When SPF was first standardised in RFC 4408 (2006), domain owners were advised to use ~all (SoftFail) rather than -all (HardFail) for the catch-all mechanism. The reasoning was pragmatic. Many organisations had complex mail flows, including forwarding services, marketing platforms or legacy servers, which might not be included in the SPF record. Using -all prematurely risked rejecting legitimate mail, so ~all allowed a “soft warning” while still signalling potential unauthorised senders. Also back then DMARC was not a thing, so getting reporting for all usage was not an option.

Over time, as awareness and tooling improved, administrators increasingly moved to -all once they were confident that all legitimate sending sources were included. +all (Pass) was sometimes used in early testing or by poorly configured domains, but it quickly became recognised as insecure because it effectively disables SPF. The ?all (Neutral) qualifier is rarely used in production. It essentially tells receivers that the domain owner is no asserting anything about unauthorised mail and provides little protection against spoofing.

In modern practice, the recommended approach is a staged deployment: start with ~all during monitoring, then move to -all once all legitimate sources are verified, ensuring maximum protection without unintended mail rejections.

DMARC & Soft Fail

With that said regarding hard fail, there is a note in the DMARC RFC 7489 that discusses SPF.

https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc7489#page-39 states in part that:

Some receiver architectures might implement SPF in advance of any DMARC operations. This means that a "-" prefix on a sender's SPF

mechanism, such as "-all", could cause that rejection to go into effect early in handling, causing message rejection before any DMARC

processing takes place. Operators choosing to use "-all" should be aware of this.SPF & Subdomain Inheritance

Does a child domain inherit the SPF record from it’s parent domain? The short answer is “no”.

The longer answer is that SPF policies do not automatically inherit from a parent domain to its subdomains. Each subdomain is evaluated independently, meaning that a parent domain’s SPF record does not apply unless the subdomain explicitly includes it. For example, if tailspintoys.ca has a valid SPF record, mail sent from emea.tailspintoys.ca will only pass SPF checks if emea.tailspintoys.ca has its own SPF record or includes the parent domain’s record using the include mechanism. RFC 7208 allows the use of the redirect modifier to simplify management, enabling a subdomain to point directly to the parent domain’s policy, but careful configuration is required to avoid conflicts or unintended failures. Administrators should explicitly plan SPF coverage for all subdomains to ensure consistent protection against spoofing and unauthorised mail.

SPF Includes

It is common to see include statements as part of SPF records. This is especially true when additional cloud services are used. It provides a layer of abstraction between the cloud vendor and customer. The customer adds the include record once. They no longer have to worry when the cloud vendor makes changes to sending infrastructure as the changes are automatically used - assuming that the vendor updates the records correct. That was an issue during the early days of COVID.

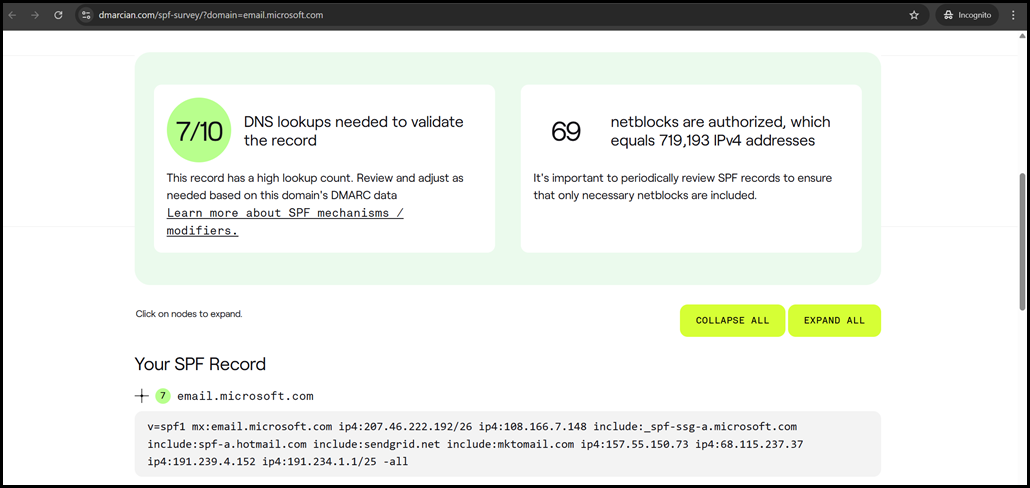

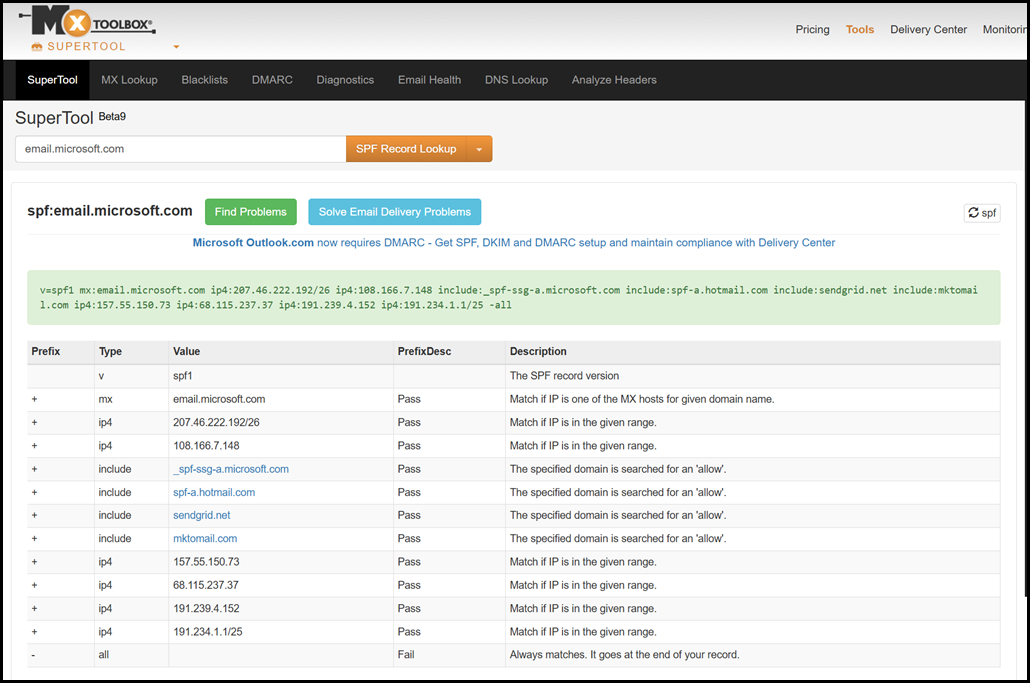

Take the email.microsoft.com subdomain. It has multiple includes, and some of them have nested include statements.

We could count them manually, or we could use a different tool to review the number of includes. One example is the DMARCIAN SPF surveyor tool.

10 Is The Number Of The Counting

As per RFC, there must be no more than 10 DNS lookups for a given domain.

SPF records perform DNS lookups to evaluate mechanisms such as include, a, mx, ptr, and exists, which can introduce overhead and potential delays in mail delivery. To prevent excessive DNS queries, RFC 7208 specifies a maximum of 10 DNS lookups per SPF check. If this limit is exceeded, the SPF evaluation fails with a "PermError," which typically causes the receiving server to treat the message as unauthenticated. This restriction has significant implications for organisations with complex mail flows, multiple third-party sending services, or nested SPF includes, as each additional include can trigger multiple lookups. Administrators must therefore design SPF records carefully, consolidating sending sources and avoiding unnecessary nesting to stay within the lookup limit while maintaining full coverage.

Enterprise SPF Strategy

I’ll split this discussion into a separate post as it would make this one significantly longer. This will cover SPF flattenign services and the the use of subdomains to provide felxabilty, scalability and security.

SPF Exp – Explanation

This is an optional explanation section of the SPF record.

v=spf1 mx -all exp=explanation._spf.%{d}

It uses the %d macro, more on that below, to dynamically add the domain to the string.

That could allow you to add a message to state that mail for the company should only be sent for the approved servers.

You could also make it a bit more spicy by doing something like:

"%{i} is not one of %{d}'s officially approved mail servers."

SPF Redirect Modifier

If multiple domains need the same SPF logic, it can make sense to define the logic once then make the additional domains redirect to that SPF record. This level of abstraction can help ease administrative burden as changes only need to be made in one place, yet all domains will then respect the changes without having to modify each record.

Let’s say that wingtiptoys.ca had multiple regional domains that should all use the same configuration. Rather than having to update all of those entries each and every time there was a change, we can maintain a single record and instruct the subdomains to use it

For example:

emea.wingtiptoys.ca. TXT "v=spf1 redirect=_spf.wingtiptoys.ca"

apac.wingtiptoys.ca. TXT "v=spf1 redirect=_spf.wingtiptoys.ca"

nam.wingtiptoys.ca. TXT "v=spf1 redirect=_spf.wingtiptoys.ca"

sam.wingtiptoys.ca. TXT "v=spf1 redirect=_spf.wingtiptoys.ca"

uk.wingtiptoys.ca. TXT "v=spf1 redirect=_spf.wingtiptoys.ca"The same methodology would also work if you had to park many SMTP domains and wanted centralised control over all of those records.

SPF Macros

The RFC allows many types of macros which allow advanced operation of the SPF record.

For example you will see these macro letters being used:

s = <sender>

l = local-part of <sender>

o = domain of <sender>

d = <domain>

i = <ip>

p = the validated domain name of <ip>

v = the string "in-addr" if <ip> is ipv4, or "ip6" if <ip> is ipv6

h = HELO/EHLO domainAnd the following are allowed but only in the EXP section

c = SMTP client IP (easily readable format)

r = domain name of host performing the check

t = current timestampIf we circle back to the expansion example listed at the top of the post, let’s now break that down.

v=spf1 include:%{i}._ip.%{h}._ehlo.%{d}._spf.Relecloud.com ~all

There are more expansion examples here.

Legacy SPF Records

When SPF was first introduced, its designers proposed a dedicated DNS resource record type, Type 99 (SPF), specifically to hold SPF policies. This was defined in RFC 4408 (2006), which allowed administrators to publish SPF records either as TXT records or using the new SPF RR type. However, adoption of Type 99 was minimal, as many DNS providers and resolvers did not implement support for it. To avoid interoperability issues, most organisations standardised on using TXT records for SPF instead. By the time RFC 7208 was published in 2014, the IETF formally deprecated DNS Type 99 for SPF, stating that all SPF policies must be published as TXT records. Today, while legacy references to the SPF RR type may still be encountered in older documentation or tooling, in practice SPF is universally deployed using DNS TXT records.

Sender ID

While not the same as SPF, it is worth noting Sender ID in this post.

Sender ID created confusion as the record syntax was the same, but it operated very differently compared to SPF. Sender ID wanted to verify the PRA (Purported Responsible Address). This would be the FROM header rather than the MAIL FROM that SPF checks.In parallel with the development of SPF, Microsoft pushed a related framework known as Sender ID, first published in 2004 and formalised in RFC 4406 (2006). Sender ID was based on SPF concepts but went further by attempting to validate the Purported Responsible Address (PRA) in the From: or Sender: headers, rather than just checking the SMTP envelope sender as SPF does. While it gained some adoption, Sender ID was controversial due to patent and licensing concerns raised by the open-source community, and because its PRA checks often conflicted with established e-mail practices such as mailing lists and forwarding. Ultimately, the wider e-mail community favoured SPF, and Sender ID saw declining support. By 2012, Microsoft itself acknowledged the shift by recommending the use of SPF over Sender ID, and when RFC 7208 replaced RFC 4408 in 2014, Sender ID was effectively sidelined.

For more Sender ID reading please read this.

Cheers,

Rhoderick -